Spoiler alert! Don’t read this if you don’t know how the Harry Potter books conclude.

I was 11 years old when Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone came out. I was too young to follow the news, but I remember a very public debate about whether or not Harry Potter encourages witchcraft and Satanism in children. As an adult, I found the same debate alive today on Twitter.com.

I knew deep down the books weren’t Satanic, and in adulthood, I realized where much of this criticism was coming from. Sola scriptura Christians tend to interpret the Good Book very literally, and they read other books the same way. Harry has a wand and uses magic spells? Occultist! They take what they read at face value, without seeing metaphor or allegory.

If you read the series with an open mind, you will see that magic in Harry Potter is a stand-in for spiritual reality: how good and evil fight for supremacy of our souls. Harry has a mystical ability to see into the evil mind of Lord Voldemort, and he struggles with whether this connection with Voldemorts means he himself is inherently evil. A major theme throughout the series is that it is not our thoughts that make us good or bad, but our choices.

This is an Orthodox Christian teaching. Logismoi is the term for intrusive negative thoughts that urge us to sin. Holy elders tell us it’s best to ignore these thoughts, and we’re not accountable for them unless we engage them and act upon them. This is similar to what Dumbledore tells Harry when his connection to Voldemort (who is a force of evil akin to Satan) disturbs him.

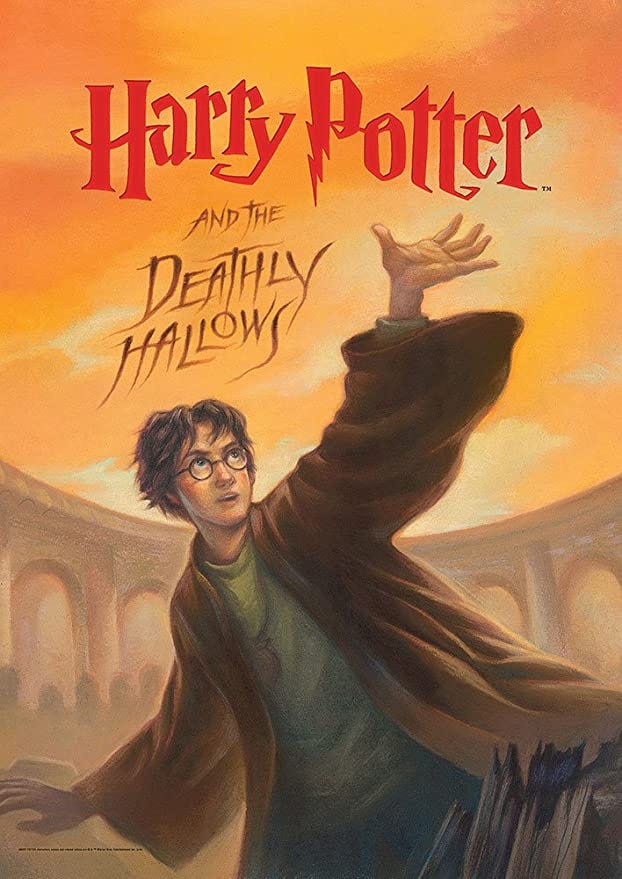

The final chapters of the series are particularly strong in Christian imagery. Voldemort makes a call for Harry to meet him in order to be killed, and Harry willingly goes to the forest, offering himself up in Jesus-like self-sacrifice. After Voldemort kills Harry, Harry finds himself in an ethereal version of King’s Cross station. King’s Cross. If Harry dying at King’s Cross isn’t the strongest reference to Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross, I am not sure what is. Harry has a conversation with Dumbledore, which clarifies much of the plot, and then he chooses to return to finish his battle with Voldemort. He resurrects and comes back to life in the forest where Voldemort just killed him.

Harry plays dead, and Voldemort delivers an "ecce homo" speech, akin to Pontius Pilate's "behold the man" speech in which he presented Jesus and mocked him. Voldemort puts an Unforgivable Curse on Harry to humiliate him and demonstrate his supremacy over The Boy Who Lived, but the spell does not affect him. Harry feels no pain. After parading Harry’s body through the forest and back to the school, Harry’s friends are horrified to see he is dead, and they commit to fighting Voldemort. But the curses Voldemort and his Death Eaters put on the students will not hold. Harry's loving self-sacrifice has protected them from Voldemort’s evil spells. Just as Jesus’ self-sacrifice protects us from the snares of the devil, Harry’s self-sacrifice protects his loved ones. Harry reveals himself as alive, and he kills Voldemort.

It’s really quite epic.

While the ending of the books makes the strongest case for Christian themes, it’s noteworthy that the wizards and witches celebrate Christmas each year throughout the series. The students at Hogwarts receive time off for the Christian holiday, give each other presents, and wish each other “Happy Christmas!” Not quite what you’d expect from a pagan book, is it? In my experience, pagans tend to avoid the name of Christ entirely, saying “Xmas” or the neutered “happy holidays.”

According to Wikipedia, J.K. Rowling identifies as a Christian, and she christened her daughter in the Church of Scotland around the time she was writing Harry Potter. In a 2012 interview, she said she belonged to the Scottish Episcopal Church. She has said that she believes in God, but has experienced doubt, and does not believe in magic or witchcraft.

This is overlooked by Christians who criticize the Harry Potter series. JRR Tolkien, a Catholic, also wrote a fantasy series that involves spells, magic, and wizards, yet his work does not receive nearly the same level of debate and criticism that Harry Potter does. In fact, Christians tend to love Lord of the Rings. I haven’t quite figured out why this double standard exists. I’d personally love to see both stories, Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings, celebrated as masterful works from Christian artists. Lord knows we could use more Christian art that appeals to youth.

Mythology or fairy tales that illustrate Christian values are, in my opinion, the best kind of art. Overtly Christian art can be off-putting to non-Christians, and at worst, it can seem preachy. It only reaches those who are already there.

The best stories contain Christianity implicitly — they point to the truth of Christ as an undercurrent. Stories that do this successfully, like Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings, touch us deeply, but we don’t know why. We intuit something about them is deeply true in our souls, even if it doesn’t compute in our heads. It registers below our conscious awareness.

People love stories like Harry Potter because good mythologies point to universal truths, and a truly great artist uses the unfamiliar in a way that enriches the familiar. The best stories take us into another world, sweep us away, and bring us back down to earth with a deeper understanding of reality. We’re better off for it.

'Looking for God in Harry Potter' went through four editions; the last one was published in 2008 after 'Deathly Hallows' and was retitled 'How Harry Cast His Spell.'

For a more esoteric interpretation of the finale, see 'The Deathly Hallows Lectures.'

For the chiastic structure of each book and the seven book series as a whole, see 'Harry Potter as Ring composition and Ring Cycle.'

For the literary allusion and the four traditional levels of reading a book, see 'Harry Potter's Bookshelf.'

Have you read "Looking for God in Harry Potter" by John Granger? He's an Orthodox Christian and makes an incredibly detailed case in the book. When the book came out, only four of the HP books were out, but based on a lot of this, Granger makes a lot of good guesses where the series was going.